from math import Dimensionality_Reduction

What’s inside this Book Chapter :

This blog is a detailed , yet lucid overview of the book chapter , “High Dimensionality Dataset Reduction Methodologies in Applied Machine Learning” from the “Taylor and Francis Book Publication (Routledge)” for the book “Data Science and Data Analytics: Opportunities and Challenges 2020”.

Read the Chapters in Detail :

Farhan Hai Khana, Tannistha Palb

a. Department of Electrical Engineering, Institute of Engineering & Management, Kolkata, India, njrfarhandasilva10@gmail.com

b. Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Institute of Engineering & Management, Kolkata, India, paltannistha@gmail.com

Abstract

A common problem faced while handling multi-featured datasets is the high amount of dimensionality that they often consist of, leading to barriers in generalized hands-on Machine Learning. These datasets also give a drastic impact on the performance of Machine Learning algorithms, being memory inefficient and frequently leading to model overfitting. It often becomes difficult to visualize or gain insightful knowledge on the data features such as presence of outliers.

This chapter will help data analysts reduce data dimensionality using various methodologies such as:

- Feature Selection using Covariance Matrix

- t-distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (t-SNE)

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Under applications of Dimensionality Reduction Algorithms with Visualizations, firstly, we introduce the Boston Housing Dataset and use the Correlation Matrix to apply Feature Selection on the strongly correlated data and perform Simple Linear Regression over the new features. Then we apply t-SNE to MNIST Handwritten Digits Dataset and use k-Nearest Neighbours (kNNs) clustering for classification. Lastly, use UCI Breast Cancer Dataset to perform PCA Analysis with Support Vector Machine (SVM) Classification. Finally, we explore the benefits of using Dimensionality Reduction Methods and provide a comprehensive overview of reduction in storage space, efficient models,feature selection guidelines, redundant data removal and outlier analysis.

Keywords : Dimensionality Reduction, Feature Selection, Covariance Matrix, PCA , t-SNE

1. Problems faced with High Dimensionality Data : An Introduction

"Dimensionality Reduction leads to a comprehensive, precise & compressed depiction of the target output variables, by reducing redundant input variables."- Farhan Khan & Tannistha Pal.

In the field of artificial intelligence, data explosion has created a plethora of input data & features to be fed into machine learning algorithms. Since most of the real-world data is multi-dimensional in nature, data scientists & data analysts require the core concepts of dimensionality reduction mechanisms for better :

(i) Data Intuition : Visualization, Outlier Detection & Noise Reduction

(ii) Performance Efficiency : Faster Training Intervals & Reduced Computational Processing Time

(iii) Generalization : Prevents Overfitting (High Variance & Low Bias)

This chapter introduces the practical working implementation of these reduction algorithms in applied machine learning.

Multiple features make it difficult to obtain valuable insights into data, as the visualization plots obtained can be 3-Dimensional at most. Due to this limitation, dependent properties/operations such as Outlier Detection and Noise Removal become more and more non-intuitive to perform on these humongous datasets. Therefore, applying dimensionality reduction helps in identifying these properties more effortlessly.

Due to this reduced/compressed form of data, faster mathematical operations such as Scaling, Classification, Regression can be performed. Also, the data is more clean and this further solves the issues of overfitting a model.

Dimensionality Reduction can be broadly classified into :

(i) Feature Selection Techniques : Feature Selection attempts to train the machine learning model by selectively choosing a subset of the original feature set based on some criteria. Hence, redundant and obsolete characteristics could be eliminated without much information loss. Examples - Correlation Matrix Thresholding & Chi Squared Test Selection.

(ii) Feature Extraction/Projection Techniques : This method projects the original input features from the high dimensional space by summarizing most statistics and removing redundant data / manipulating to create new relevant output features with reduced dimensionality (fewer dimensional space). Examples - Principle Component Analysis (PCA) , Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), t-distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding(t-SNE) & Isometric Mapping (IsoMap).

However, we have limited our discussion to Correlation Matrices, PCA & t-SNE only, as covering all such techniques is beyond the scope of this book chapter.

2. Dimensionality Reduction Algorithms with Visualizations

2.1 Feature Selection using Covariance Matrix

Objective : Introduce Boston Housing Dataset and use the obtained Correlation Matrix to apply Feature Selection on the strongly positive correlated data and perform Regression over the selective features.

2.1.1 Importing the Modules

We will need 3 datasets for this chapter, each of which have been documented on our github repository. Hence we will create a local copy (clone) of that repo here.

!git clone https://github.com/khanfarhan10/DIMENSIONALITY_REDUCTION.git

Cloning into 'DIMENSIONALITY_REDUCTION'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 14, done.[K

remote: Counting objects: 100% (14/14), done.[K

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (12/12), done.[K

remote: Total 14 (delta 1), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0[K

Unpacking objects: 100% (14/14), done.

Firstly we will import all the necessary libraries that we will be requiring for Dataset Reductions.

import numpy as np # Mathematical Functions , Linear Algebra, Matrix Operations

import pandas as pd # Data Manipulations, Data Analysis/Storing/Preparation

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Simple Data Visualization , Basic Plotting Utilities

plt.style.use("dark_background") #just a preference of the authors, adds visual attractiveness

import seaborn as sns # Advanced Data Visualization, High Level Figures Interfacing

%matplotlib inline

# used for Jupyter Notebook Plotting

#%matplotlib notebook # This can be used as an alternative as the plots obtained will be interactive in nature.

Initial Pseudo Random Number Generator Seeds:

In Applied Machine Learning, it is essential to make experiments reproducable and at the same time keeping weights as completely random. The Seed of a Pseudo Random Number Generator (PRNG) acheives the exact same task by initializing values with the same conditions everytime a program is executed. We have used a constant value (universal seed) of 42 throughout the course of this chapter.

univ_seed=42

np.random.seed(univ_seed)

2.1.2 The Boston Housing Dataset

The Dataset is derived from information collected by the U.S. Census Service concerning housing in the area of Boston Mass. The Boston dataframe has 506 rows and 14 columns. The MEDV variable is the target variable.

Columns / Variables in order:

CRIM- per capita crime rate by townZN- proportion of residential land zoned for lots over 25,000 sq.ft.INDUS- proportion of non-retail business acres per townCHAS- Charles River dummy variable (= 1 if tract bounds river; 0 otherwise)NOX- nitric oxides concentration (parts per 10 million)RM- average number of rooms per dwellingAGE- proportion of owner-occupied units built prior to 1940DIS- weighted distances to five Boston employment centresRAD- index of accessibility to radial highwaysTAX- full-value property-tax rate per $10,000PTRATIO- pupil-teacher ratio by townB- \(1000*(B_{k} - 0.63)^{2}\) where \(B_{k}\) is the proportion of blacks by townLSTAT- % lower status of the populationMEDV- Median value of owner-occupied homes in $1000’s

Importing the dataset :

from sklearn.datasets import load_boston # scikit learn has an inbuilt dataset library which includes the boston housing dataset

boston_dataset = load_boston() # the boston_dataset is a dictionary of values containing the data

df = pd.DataFrame(boston_dataset.data, columns=boston_dataset.feature_names) # creating a dataframe of the boston_dataest

df['MEDV'] = boston_dataset.target # adding the target variable to the dataframe

df.head(4) # printing the first 4 columns of the dataframe

| CRIM | ZN | INDUS | CHAS | NOX | RM | AGE | DIS | RAD | TAX | PTRATIO | B | LSTAT | MEDV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.00632 | 18.0 | 2.31 | 0.0 | 0.538 | 6.575 | 65.2 | 4.0900 | 1.0 | 296.0 | 15.3 | 396.90 | 4.98 | 24.0 |

| 1 | 0.02731 | 0.0 | 7.07 | 0.0 | 0.469 | 6.421 | 78.9 | 4.9671 | 2.0 | 242.0 | 17.8 | 396.90 | 9.14 | 21.6 |

| 2 | 0.02729 | 0.0 | 7.07 | 0.0 | 0.469 | 7.185 | 61.1 | 4.9671 | 2.0 | 242.0 | 17.8 | 392.83 | 4.03 | 34.7 |

| 3 | 0.03237 | 0.0 | 2.18 | 0.0 | 0.458 | 6.998 | 45.8 | 6.0622 | 3.0 | 222.0 | 18.7 | 394.63 | 2.94 | 33.4 |

Library Information :

The variable boston_dataset is python dictionary returned via the scikit-learn library with the following keys:

- data : The input values of the dataset.

- target : The output variable of the dataset.

- feature_names : The name of the feature variables as an array.

- DESCR : A brief description of the dataset.

- filename : Local location of the file with it’s full path.

You can access each key’s values using boston_dataset.key_name as we used to create a pandas dataframe. You can read the official scikit learn datasets documentation and get to know about embedded datasets.

Alternatively :

You can also run the following code, provided you have cloned our github repository.

df= pd.read_excel("/content/DIMENSIONALITY_REDUCTION/data/Boston_Data.xlsx")

Also, with a working internet connection, you can run :

df= pd.read_excel("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/khanfarhan10/DIMENSIONALITY_REDUCTION/master/data/Boston_Data.xlsx")

–OR–

df= pd.read_excel("https://github.com/khanfarhan10/DIMENSIONALITY_REDUCTION/blob/master/data/Boston_Data.xlsx?raw=true")

Data Insights :

You might want to try df.isnull().sum() , df.info() , df.describe() to get the columnwise null values, dataframe information and row-wise description respectively. However , here the data provided is clean and free from such issues which would be needed to be processed/handled inspectionally.

2.1.3 Perform Basic Data Visualization

Data Visualization is the key to visual data insights and can provide useful analytics about the data. Here in the following code snippet, we will find out the distribution of each columns (feature & target) in the data.

df.hist(bins=30,figsize=(20,10),grid=False,color="crimson"); # distribution of each column

Data Visualization Tips :

For more color palettes visit : Matplotlib Named Colours.

Almost all the visualizations used in this chapter from Pandas and Seaborn can be saved to high quality pictures using plt.savefig("fig_name.png",dpi=600)

2.1.4 Pearson Coefficient Correlation Matrix

The Pearson Correlation Coefficient (also known as the Pearson R Test) is a very useful statistical formulae that measures the strength between features and relations.

Mathematically,

\[r_{xy}=\frac{N \Sigma x y-(\Sigma x)(\Sigma y)}{\sqrt{\left[N \Sigma x^{2}-(\Sigma x)^{2}\right]\left[N \Sigma y^{2}-(\Sigma y)^{2}\right]}}\]where

\(r_{xy}\) = Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient between variables x & y

\(N\) = number of pairs of x & y variables in the data

\(\Sigma x y\) = sum of products between x & y variables

\(\Sigma x\) = sum of x values

\(\Sigma y\) = sum of y values

\(\Sigma x^{2}\) = sum of squared x values

\(\Sigma y^{2}\) = sum of squared y values

For all feaure variables \(f_{i}\) \(\epsilon\) \(F\) arranged in any order , with \(n(F) = N\)

The Correlation Coefficient Matrix is \(M_{N \times N}\) , where

\(M_{ij}\) = \(r_{ij}\) , \(i,j\) \(\epsilon\) \(F\)

We will now use Pandas to get the correlation matrix and plot a heatmap using Seaborn.

correlation_matrix = df.corr().round(2) #default method = ‘pearson’, also available : ‘kendall’, ‘spearman’ correlation coefficients

plt.figure(figsize=(20,10)) #set the figure size to display

sns.heatmap(data=correlation_matrix,cmap="inferno", annot=True) # annot = True to print the values inside the squares

plt.savefig("Correlation_Data.png",dpi=600)

2.1.5 Detailed Correlation Matrix Analysis

The correlation coefficient ranges from -1 to 1. If the value is close to 1, it means that there is a strong positive correlation between the two variables and both increase or decrease simultaneously. When it is close to -1, the relationship between the variables is negatively correlated, or as one value increases, the other decreases.

Observations:

To fit a linear regression model, we select those features which have a high correlation with our target variable MEDV. By looking at the correlation matrix we can see that RM has a strong positive correlation with MEDV (0.7) where as LSTAT (-0.74) has a high negative correlation with MEDV. An important point in selecting features for a linear regression model is to check for Multi Collinearity : features that are strongly correlated to other features and are therefore redundant. The features RAD, TAX have a correlation of 0.91. These feature pairs are strongly correlated to each other . We should not select both these features together for training the model. The same goes for the features DIS and AGE which have a correlation of -0.75. Except for a manual analysis of the correlation, the function below computes the strongly correlated features to the target variable MEDV :

thres_range=(-0.7,0.7) # provide the upper and lower limits for thresholding the strongly correlated features

target_variable="MEDV" # provide the target variable name

def get_strong_corr(correlation_matrix,target_variable,thres_range=(-0.65,0.65)):

"""

Get the strongly positive and strongly negatively correlated components from the provided correlation matrix.

Assigns values inside boundary to 0 and returns non zero entries as a Pandas Series.

correlation_matrix : The correlation matrix obtained from the data.

target_variable : The name of the target variable that we need to calculate the correlation for.

thres_range : The thresholding range for the calculation of strongly correlated data.

"""

thres_min,thres_max=thres_range # assign minimum and maximum values passed to threshold

target_row=correlation_matrix[target_variable] # get the row with the target variable name

target_row[(target_row > thres_min) & (target_row < thres_max)]=0 # assign values out of given threshold to zero

indices_thresholded=target_row.to_numpy().nonzero() # remove the zero values from the filtered target row and get indices

strong_corr=list(correlation_matrix.columns[indices_thresholded]) # extract feature names from their respective indices

if target_variable in strong_corr: strong_corr.remove(target_variable)# correlation of target variable with itself is always 1, remove it.

return target_row[strong_corr] # return the strongly correlated features with their values

strong_corr=get_strong_corr(correlation_matrix,target_variable,thres_range)

print(strong_corr)

RM 0.70

LSTAT -0.74

Name: MEDV, dtype: float64

Python Code Documentation - Docstrings :

Triple quoted strings ("""String""") after a function declaration in Python account for a function’s documentation and are referred to as Docstrings. These can be retrieved later and add the advantage of asking help towards the working of a function.

Create Docstring :

def function_name(arguments):

"""Function Documentation""""

Retrieve Helper Docstring :

help(function_name)

For information about Docstrings visit : Docstring Conventions. For example you could run the following command:

help(get_strong_corr)

Based on the above observations and discussions we will use RM and LSTAT as our features. Using a scatter plot let’s see how these features vary with MEDV.

plt.figure(figsize=(25,10)) # initialize the figure with a figure size

features = ['LSTAT', 'RM'] # features to display over the dataset

for i, col in enumerate(features): # loop over the features with count

plt.subplot(1, len(features) , i+1) # subplotting

x = df[col] # getting the column values from the dataframe

plt.scatter(x, target, marker='o',color="cyan") # performing a scatterplot in matplotlib over x & target

plt.title("Variation of "+target_variable+" w.r.t. "+col) # setting subplot title

plt.xlabel(col) # setting the xlabels and ylabels

plt.ylabel(target_variable)

2.1.6 3-Dimensional Data Visualization

The added advantage of performing Dimensionality Reduction is that 3-D visualizations are now possible over the input features (LSTAT & RM) and the target output (MEDV). These visual interpretations of the data help us obtain a concise overview of the model hypothesis complexity that needs to be considered to prevent overfitting.

import plotly.graph_objects as go # plotly provides interactive 3D plots

from plotly.graph_objs.layout.scene import XAxis, YAxis, ZAxis

df_sampled= df.sample(n = 100,random_state=univ_seed) # use random sampling to avoid cumbersome overcrowded plots

LSTAT, RM, MEDV = df_sampled["LSTAT"], df_sampled["RM"], df_sampled["MEDV"]

# set the Plot Title , Axis Labels , Tight Layout , Theme

layout = go.Layout(

title="Boston Dataset 3-Dimensional Visualizations",

scene = dict( xaxis = XAxis(title='LSTAT'), yaxis = YAxis(title='RM'), zaxis = ZAxis(title='MEDV'), ),

margin=dict(l=0, r=0, b=0, t=0),

template="plotly_dark"

)

# create the scatter plot with required hover information text

trace_scatter= go.Scatter3d(

x=LSTAT,

y=RM,

z=MEDV,

mode='markers',

marker=dict(

size=12,

color=MEDV,

showscale=True, # set color to an array/list of desired values

colorscale='inferno', # choose a colorscale: viridis

opacity=0.8

),

text= [f"LSTAT: {a}<br>RM: {b}<br>MEDV: {c}" for a,b,c in list(zip(LSTAT,RM,MEDV))],

hoverinfo='text'

)

#get the figure using the layout on the scatter trace

fig = go.Figure(data=[trace_scatter],layout=layout)

fig.write_html("Boston_3D_Viz.html") # save the figure to html

fig.show() # display the figure

Saving Interactive Plots :

To save the 3D plots externally for future purposes use fig.write_html("Boston_3D_Viz.html") to save the interactive plots to HTML files accessible by internet browsers.

Conclusions based on Visual Insights :

-

Home Prices(

MEDV) tend to decrease with the increase inLSTAT. The curve follows a linear - semi-quadratic equation in nature. -

Home Prices(

MEDV) tend to increase with the increase inRMlinearly. There are few outliers present in the dataset as clearly portrayed by the 3-D Visualization.

2.1.7 Extracting the Features and Target

Extract the Input Feature Variables in \(X\) & Output Target Variable in \(y\).

X = pd.DataFrame(np.c_[df['LSTAT'], df['RM']], columns = ['LSTAT', 'RM']) # concatenate LSTAT and RM columns using numpy np.c_ function

y = df['MEDV'] # store the target column median value of homes (MEDV) in y

print('Dataframe Shapes : ','Shape of X : {} , Shape of y : {}'.format(X.shape,y.shape)) # print the shapes of the Input and Output Variables

X=X.to_numpy() # Convert the Input Feature DataFrame X to a NumPy Array

y=y.to_numpy() # Convert the Output Target DataFrame y to a NumPy Array

y=y.reshape(-1,1) # Shorthand method to reshape numpy array to single column format

print('Array Shapes : ','Shape of X : {} , Shape of y : {}'.format(X.shape,y.shape)) # print the shapes of the Input and Output Variables

Dataframe Shapes : Shape of X : (506, 2) , Shape of y : (506,)

Array Shapes : Shape of X : (506, 2) , Shape of y : (506, 1)

2.1.8 Feature Scaling

Feature scaling/standardization helps machine learning models converge faster to a global optima by transforming the data to have zero mean and a unit variance of 1 hence making the data unitless.

\[x^{\prime}=\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}\]where

\(x\)= Input Feature Variable

\(x^{\prime}\) = Standardized Value of \(x\)

\(\mu\)= Mean value of \(x\) (\(\bar{x}\))

\(\sigma=\sqrt{\frac{\sum\left(x_{i}-\mu\right)^{2}}{N}}\) (Standard Deviation)

\(x_{i}\) = Each value in \(x\)

\(N\) = No. of Observations in \(x\) (Size of \(x\))

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler # import the Scaler from the Scikit-Learn Library

scaler_x = StandardScaler() # initialize an instance of the StandardScaler for Input Features (X)

X_scaled= scaler_x.fit_transform(X) # fit the Input Features (X) to the transform

scaler_y = StandardScaler() # initialize another instance of the StandardScaler for Output Target (y)

y_scaled = scaler_y.fit_transform(y) # fit the Output Target (y) to the transform

2.1.9 Create Training and Testing Dataset

Splitting the Data into Training (70%) and Testing (30%) Sets:

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split # import train test split functionality from the Scikit-Learn Library

# perform the split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_scaled, y_scaled, test_size = 0.3, random_state=univ_seed)

# print out the shapes of the Training and Testing variables

print('Shape of X_train : {} , Shape of X_test : {}'.format(X_train.shape,X_test.shape))

print('Shape of y_train : {} , Shape of y_test : {}'.format(y_train.shape,y_test.shape))

Shape of X_train : (354, 2) , Shape of X_test : (152, 2)

Shape of y_train : (354, 1) , Shape of y_test : (152, 1)

2.1.10 Training and Evaluating Regression Model with Reduced Dataset

Multivariate Linear Regression :

Multivariate Linear Regression is a linear approach to modelling the relationship (mapping) between various dependent input feature variables & the independent output target variable.

Model Training - Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) :

Here we will attempt to fit a linear regression model which would map the input features \(x_{i}\) (LSTAT & RM) to \(y\) (MEDV). Hence the model hypothesis :

\(h_{\Theta}(x)=\Theta_{0} + \Theta_{1}x_{1} + \Theta_{2}x_{2}\)

where,

\(y\) = Output Target Variable MEDV

\(x_{1}\) = Input Feature Variable LSTAT

\(x_{2}\) = Input Feature Variable RM

\(\Theta\) = Model Parameters (to obtain)

We perform Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression using the scikit-learn library to obtain \(\Theta_{i}\).

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression # import the Linear Regression functionality from the Scikit-Learn Library

lin_model = LinearRegression() # Create an Instance of LinearRegression function

lin_model.fit(X_train, y_train) # Fit the Linear Regression Model

points_to_round=2 # Number of points to round off the results

# get the list of model parameters in the theta variable

theta= list(lin_model.coef_.flatten().round(points_to_round))+list(lin_model.intercept_.flatten().round(points_to_round))

print("Model Parameters Obtained : ",theta) # merge the values of theta 1 and theta 2 (coef_) and the value of theta 0 (intercept_)

Model Parameters Obtained : [-0.52, 0.38, 0.01]

def get_model_params(theta,features,target_variable):

"""Pretty Print the Features with the Model Parameters"""

text = target_variable + " = " + str(theta[0])

for t, x in zip ( theta[1:], features) :

text += " + "+ str(t) + " * " + str(x)

return text

features=['LSTAT','RM'] # features names

print(get_model_params(theta,features,target_variable)) # display the features with the model parameters

MEDV = -0.52 + 0.38 * LSTAT + 0.01 * RM

Model Evaluation - Regression Metrics :

We need to calculate the following values in order to evaluate our model.

- Mean Absolute Error(MAE)

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

- R-Squared Value (coefficient of determination)

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error, mean_absolute_error, r2_score

# import necessary evaluation scores/metrics from the Scikit-Learn Library

def getevaluation(model, X_subset,y_subset,subset_type="Train",round_scores=None):

"""Get evaluation scores of the Train/Test values as specified"""

y_subset_predict = model.predict(X_subset)

rmse = (np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(y_subset, y_subset_predict)))

r2 = r2_score(y_subset, y_subset_predict)

mae=mean_absolute_error(y_subset, y_subset_predict)

if round_scores!=None:

rmse=round(rmse,round_scores)

r2=round(r2,round_scores)

mae=round(mae,round_scores)

print("Model Performance for {} subset :: RMSE: {} | R2 score: {} | MAE: {}".format(subset_type,rmse,r2,mae))

getevaluation(model=lin_model,X_subset=X_train,y_subset=y_train,subset_type="Train",round_scores=2)

getevaluation(model=lin_model,X_subset=X_test,y_subset=y_test,subset_type="Test ",round_scores=2)

Model Performance for Train subset :: RMSE: 0.6 | R2 score: 0.65 | MAE: 0.43

Model Performance for Test subset :: RMSE: 0.59 | R2 score: 0.6 | MAE: 0.44

2.1.11 Limitations of the Correlation Matrix Analysis

Correlation Coefficients are a vital parameter when applying Linear Regression on your Datasets. However it is limited as :

- Only LINEAR RELATIONSHIPS are being considered as candidates for mapping of the target to the features. However, most mappings are non-linear in nature.

- Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression is SUSCEPTABLE TO OUTLIERS and may learn an inaccurate hypothesis from the noisy data.

- There may be non-linear variables other than the ones chosen with Pearson Coefficient Correlation Thresholding, which have been discarded, but do PARTIALLY INFLUENCE the output variable.

- A strong correlation assumes a direct change in the input variable would reflect back immediately into the output variable, but there exist some variables that are SELECTIVELY INDEPENDENT in nature yet they provide a suitably high value of the correlation coefficient.

2.2 t-distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (t-SNE)

Objective : Introduce MNIST Handwritten Digits Dataset and obtained the reduced t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding) Features to perform k-NN (k-Nearest Neighbours) Classification over the digits.

2.2.1 The MNIST Handwritten Digits Dataset

The MNIST database (Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology Database) is a large database of handwritten digits which is widely used worldwide as a benchmark dataset, often used by various Machine Learning classifiers.

The MNIST database contains 60,000 training images and 10,000 testing images & each image size is 28x28 pixels with all images being grayscale.

Importing the dataset :

The MNIST dataset is built into scikit-learn and can be obtained from its datasets API from OpenML using the following code :

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml # to fetch the dataset

mnist = fetch_openml("mnist_784") # get the dataset from openml.org

X = mnist.data / 255.0 # since images are in the range 0-255 , normalize the features

y = mnist.target # store the target

print("Size of Input Variable (X) : ",X.shape,"Size of Target Variable (y) : ", y.shape) # get shapes

feat_cols = [ 'pixel'+str(i) for i in range(X.shape[1]) ] # convert num to pixelnum for column names

df = pd.DataFrame(X,columns=feat_cols) # create dataframe using variables

df['y'] = y # store the target in dataframe

df['label'] = df['y'].apply(lambda i: str(i)) # convert numerical values to string literals

X, y = None, None # calling destructor by reassigning, saves space

print('Size of the dataframe: {}'.format(df.shape)) # get dataframe shape

Size of Input Variable (X) : (70000, 784) Size of Target Variable (y) : (70000,)

Size of the dataframe: (70000, 786)

2.2.2 Perform Exploratory Data Visualization

Since the dataframe is not human readable, we will view the rows as images from the dataset. To choose the images we will use a random permutation :

rndperm = np.random.permutation(df.shape[0]) # random permutation to be used later for data viz

plt.gray() # set the colormap to “gray”

fig = plt.figure( figsize=(20,9) ) # initilaize the figure with the figure size

for i in range(0,15):

# use subplots to get 3x5 matrix of random handwritten digit images

ax = fig.add_subplot(3,5,i+1, title="Digit: {}".format(str(df.loc[rndperm[i],'label'])) )

ax.matshow(df.loc[rndperm[i],feat_cols].values.reshape((28,28)).astype(float))

ax.set_xticks([]) # set the xticks and yticks as blanks

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.show() # display the figure

2.2.3 Random Sampling of the Large Dataset

Since the dataset is huge , we will use random sampling from the dataset to reduce computational time keeping the dataset characteristics at the same time. The operations performed on the original dataset can now be performed on this sampled dataset with faster results & similar behaviour.

N = 10000 # number of rows to be sampled

df_subset = df.loc[rndperm[:N],:].copy() # generate random permutation of number of rows and copy them to subset dataframe

data_subset = df_subset[feat_cols].values # get the numpy array of this dataframe and store it is subset data

2.2.4 T-Distributed Stochastic Neighbouring Entities (t-SNE) - An Introduction

t-SNE is a nonlinear dimensionality reduction algorithm that is commonly used to reduce complex problems with linearly nonseparable data.

Linearly Nonseperable Data refers to the data that cannot be separated by any straight line such as :

2.2.5 Probability & Mathematics behind t-SNE

Provided a set of features \(x_{i}\) , t-SNE computes the proportional probability (\(p_{ij}\)) of object similarity between \(x_{i}\) & \(x_{j}\) using the following relation :

For \(i≠j\),

\[p_{j \mid i}=\frac{\exp \left(-\left\|\mathbf{x}_{i}-\mathbf{x}_{j}\right\|^{2} / 2 \sigma_{i}^{2}\right)}{\sum_{k \neq i} \exp \left(-\left\|\mathbf{x}_{i}-\mathbf{x}_{k}\right\|^{2} / 2 \sigma_{i}^{2}\right)}\]For \(i=j\),

\[p_{i \mid i} = 0\]where \(\sigma^{2}\) is the variance.

Further \(p_{ij}\) is calculated with the help of the bisection method :

\[p_{i j}=\frac{p_{j \mid i}+p_{i \mid j}}{2 N}\]Also notice that :

- \[\sum_{j} p_{j \mid i}=1 \text { for all } i\]

- \[p_{ij}=p_{ji}\]

- \[p_{ii}=0\]

- \[\sum_{i,j} p_{ij}=1\]

In simple terms,

Also, \(x_{i}\) would pick \(x_{j}\) as its neighbor if neighbors were picked in proportion to their probability density under a Gaussian centered at \(x_{i}\).

t-Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) minimizes the divergence between two distributions: a distribution that measures pairwise similarities of the input objects and a distribution that measures pairwise similarities of the corresponding low-dimensional points in the embedding.

- Van der Maaten & Hinton.

Hence, the t-SNE algorithm generates the reduced feature set by synchronizing the probability distributions of the original data and the best represented low dimensional data.

t-SNE Detailed Information :

For detailed visualization and hyperparameter tuning (perplexity, number of iterations) for t-SNE visit Distill!

2.2.6 Implementing & Visualizing t-SNE in 2-D

Here we will obtain a 2-Dimensional view of the t-SNE components after fitting to the dataset.

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE # import TSNE functionality from the Scikit-Learn Library

tsne = TSNE(n_components=2, verbose=1, perplexity=40, n_iter=300, random_state = univ_seed)

# Instantiate the TSNE Object with Hyperparameters

tsne_results_2D = tsne.fit_transform(data_subset) # Fit the dataset to the TSNE object

[t-SNE] Computing 121 nearest neighbors...

[t-SNE] Indexed 10000 samples in 1.062s...

[t-SNE] Computed neighbors for 10000 samples in 178.446s...

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 1000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 2000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 3000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 4000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 5000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 6000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 7000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 8000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 9000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 10000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Mean sigma: 2.117975

[t-SNE] KL divergence after 250 iterations with early exaggeration: 85.793327

[t-SNE] KL divergence after 300 iterations: 2.802306

reduced_df=pd.DataFrame(np.c_[df_subset['y'] ,tsne_results_2D[:,0], tsne_results_2D[:,1]],

columns=['y','tsne-2d-one','tsne-2d-two' ])

# store the TSNE results in a dataframe

reduced_df.head(4) #display the first 4 rows in the saved dataframe

| y | tsne-2d-one | tsne-2d-two | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8 | -1.00306 | -0.128447 |

| 1 | 4 | -4.42499 | 3.18461 |

| 2 | 8 | -6.95557 | -3.65212 |

| 3 | 7 | -1.80255 | 7.62499 |

fig=plt.figure(figsize=(16,10)) # initialize the figure and set the figure size

reduced_df_sorted=reduced_df.sort_values(by='y', ascending=True)

# sort the dataframe by labels for better visualization results

sns.scatterplot(

x="tsne-2d-one", y="tsne-2d-two", # provide the x & y dataframe columns

hue="y", # provide a hue column from the target variable

palette=sns.color_palette("tab10", 10), # Color Palette for Seaborn ( Other Sets - hls, rocket, icefire , Spectral )

data=reduced_df_sorted, # provide the dataframe

legend="full", # display the full legend

alpha=1) # set the transparency of points to 0% (opaques points)

# plot the scatter plot using Seaborn with parameters

# set the plot metadata such as legend title and plot title

plt.legend(title="Target Digits (y)")

plt.title("t-SNE Plot for MNIST Handwritten Digit Classification",fontsize=20)

Colour Palettes : Seaborn

For a list of colour variations assigned to the plot shown visit Seaborn Colour Palettes.

2.2.7 Implementing & Visualizing t-SNE in 3-D

Obtaining a 3-Dimensional Overview to t-SNE is essential for better visual observations than the 2-Dimensional overview. The below code is dedicated to the better understanding of t-SNE algorithm.

tsne = TSNE(n_components=3, verbose=1, perplexity=40, n_iter=300, random_state = univ_seed)

# Instantiate the TSNE Object with Hyperparameters for 3D visualization

tsne_results_3D = tsne.fit_transform(data_subset) # Fit the dataset to the 3D TSNE object

[t-SNE] Computing 121 nearest neighbors...

[t-SNE] Indexed 10000 samples in 1.027s...

[t-SNE] Computed neighbors for 10000 samples in 180.065s...

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 1000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 2000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 3000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 4000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 5000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 6000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 7000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 8000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 9000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Computed conditional probabilities for sample 10000 / 10000

[t-SNE] Mean sigma: 2.117975

[t-SNE] KL divergence after 250 iterations with early exaggeration: 85.736298

[t-SNE] KL divergence after 300 iterations: 2.494533

reduced_df['tsne-3d-one']=tsne_results_3D[:,0] # add TSNE 3D results to the dataframe

reduced_df['tsne-3d-two']=tsne_results_3D[:,1]

reduced_df['tsne-3d-three']=tsne_results_3D[:,2]

reduced_df.tail(4) # display the last 4 rows of the dataframe

| y | tsne-2d-one | tsne-2d-two | tsne-3d-one | tsne-3d-two | tsne-3d-three | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9996 | 8 | -4.65108 | -1.11998 | 0.802126 | -3.50290 | -2.521323 |

| 9997 | 3 | 0.219714 | -4.02806 | -3.190483 | 1.40809 | -3.643212 |

| 9998 | 8 | -0.110848 | -5.17118 | -2.957494 | 1.16458 | -2.184380 |

| 9999 | 3 | -2.01736 | -2.94456 | -1.057328 | -0.79992 | -4.963109 |

import plotly.express as px # import express plotly for interactive visualizations

df_sampled= reduced_df.sample(n = 500,random_state=univ_seed) # perform random sampling of the dataframe

df_sampled_sorted=df_sampled.sort_values(by='y', ascending=True) # sort the dataframe for better visualizations w.r.t. target variable

fig = px.scatter_3d(df_sampled_sorted, x='tsne-3d-one', y='tsne-3d-two', z='tsne-3d-three',

color='y', template="plotly_dark")

# make a 3 dimensional scatterplot using plotly express

fig.write_html("MNIST_Handwritten_Digits_Dataset_tSNE_3D_Viz.html") # save the plot to interactive html

fig.show() # dsiplay the figure

2.2.8 Applying k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) on the t-SNE MNIST Dataset

The k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) classifier determines the category of an observed data point by majority vote of the k closest observations around it.

The measure of this “closeness” of the data is obtained mathematically using some distance metrics. For our purpose, we will be using the Euclidean Distance(d), which is simply the length of the straight line connecting two distant points \(p_{1}\) & \(p_{2}\).

In 1-Dimension, for points \(p_{1}(x_{1})\) & \(p_{2}(x_{2})\):

\[d(p_{1}, p_{2})=\sqrt{\left(x_{1}-x_{2}\right)^{2}}=|x_{1}-x_{2}|\]In 2-Dimensions, for points \(p_{1}(x_{1},y_{1})\) & \(p_{2}(x_{2},y_{2})\):

\[d(p_{1}, p_{2})=\sqrt{\left(x_{1}-x_{2}\right)^{2}+\left(y_{1}-y_{2}\right)^{2}}\]In 3-Dimensions, for points \(p_{1}(x_{1},y_{1},z_{1})\) & \(p_{2}(x_{2},y_{2},z_{2})\):

\[d(p_{1}, p_{2})=\sqrt{\left(x_{1}-x_{2}\right)^{2}+\left(y_{1}-y_{2}\right)^{2}+\left(z_{1}-z_{2}\right)^{2}}\]Based on the calculated distance with \(x\), \(y\) & \(z\) coordinates the algorithm pulls out the closest k neighbors and then does a majority voting for the predictions. However, the value of k diversely affects the algorithm and is an important hyperparameter.

2.2.9 Data Preparation - Extracting the Features and Target

Extract the Input Feature Variables in \(X\) & Output Target Variable in \(y\).

X=reduced_df[["tsne-2d-one", "tsne-2d-two"]].values # extract the Generated Features with TSNE

y=reduced_df["y"].values # extract target values in y

print("X Shape : ", X.shape , "y Shape : ", y.shape) # display the shapes of the variables

X Shape : (10000, 2) y Shape : (10000,)

2.2.10 Create Training and Testing Dataset

Splitting the data into Training (80%) & Testing (20%) Sets:

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split( X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=univ_seed)

# perform the train test split

print ('Train set:', X_train.shape, y_train.shape) # get respective shapes

print ('Test set:', X_test.shape, y_test.shape)

Train set: (8000, 2) (8000,)

Test set: (2000, 2) (2000,)

2.2.11 Choosing the k-NN hyperparameter - k

Obtaining the predictions and accuracy scores for each k :

Since the optimal value of k for the k-Nearest Neighbors Classifier is not known to us initially, hence we will attempt to find the value of k from a range that provides the best test set evaluation for the model. The model accuracy is the percentage score of correctly classified predictions.

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier # import the kNN Classifier from the Scikit-Learn Library

from sklearn import metrics # import the metrics from the Scikit-Learn Library

Ks = 20+1 # number of k values to test for

# initialize the accuracies

mean_acc = np.zeros((Ks-1))

mean_acc_train= np.zeros((Ks-1))

std_acc = np.zeros((Ks-1))

std_acc_train = np.zeros((Ks-1))

for n in range(1,Ks):

#Train Model and Predict

neigh = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors = n).fit(X_train,y_train)

yhat=neigh.predict(X_test)

mean_acc[n-1] = metrics.accuracy_score(y_test, yhat) # gets the test accuracy

y_pred=neigh.predict(X_train)

mean_acc_train[n-1] = metrics.accuracy_score(y_train,y_pred) # gets the train accuracy

std_acc[n-1]=np.std(yhat==y_test)/np.sqrt(yhat.shape[0]) # compute the standard deviations

std_acc_train[n-1]=np.std(y_pred==y_train)/np.sqrt(y_pred.shape[0])

print("MEAN ACCURACY") # print the mean training and testing accuracy

length=len(mean_acc)

for i in range(length):

test_acc='{0:.3f}'.format(round(mean_acc[i],3))

train_acc='{0:.3f}'.format(round(mean_acc_train[i],3))

print("K=",f"{i+1:02d}"," Avg. Test Accuracy=",test_acc," Avg. Train Accuracy=",train_acc)

MEAN ACCURACY

K= 01 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.827 Avg. Train Accuracy= 1.000

K= 02 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.840 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.921

K= 03 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.854 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.917

K= 04 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.863 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.902

K= 05 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.870 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.902

K= 06 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.870 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.895

K= 07 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.872 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.894

K= 08 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.871 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.890

K= 09 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.866 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.889

K= 10 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.868 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.888

K= 11 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.869 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.886

K= 12 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.871 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.885

K= 13 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.871 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.885

K= 14 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.870 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.883

K= 15 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.871 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.883

K= 16 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.869 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.881

K= 17 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.870 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.881

K= 18 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.870 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.880

K= 19 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.869 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.880

K= 20 Avg. Test Accuracy= 0.868 Avg. Train Accuracy= 0.878

Obtaining the best value for k :

The optimal value for k can be found graphically and analytically as shown :

# get the best value for k

print( "The best test accuracy was", mean_acc.max(), "with k=", mean_acc.argmax()+1)

print( "The corresponding training accuracy obtained was :",mean_acc_train[mean_acc.argmax()])

plt.figure(figsize=(15,7.5)) # set the figure size

# plot the mean accuracies and their standard deviations

plt.plot(range(1,Ks),mean_acc_train,'r',linewidth=5)

plt.plot(range(1,Ks),mean_acc,'g',linewidth=5)

plt.fill_between(range(1,Ks),mean_acc - 1 * std_acc,mean_acc + 1 * std_acc, alpha=0.10)

plt.fill_between(range(1,Ks),mean_acc_train - 1 * std_acc_train,mean_acc_train + 1 * std_acc_train, alpha=0.10)

# plot the points for Best Test Accuracy & Corresponding Train Accuracy.

plt.scatter( mean_acc.argmax()+1, mean_acc.max())

plt.scatter( mean_acc.argmax()+1, mean_acc_train[mean_acc.argmax()])

# set up the legend

plt.legend(('Train_Accuracy ','Test_Accuracy ', '+/- 3xstd_test','+/- 3xstd_train','BEST_TEST_ACC','CORRESPONDING_TRAIN_ACC'))

# set plot metadata

plt.xticks(ticks=list(range(Ks)),labels=list(range(Ks)) )

plt.ylabel('Accuracy ')

plt.xlabel('Number of Neighbors (K)')

plt.title("Number of Neigbors Chosen vs Mean Training and Testing Accuracy Score",fontsize=20)

plt.tight_layout()

#this plot clearly shows that initially the model does overfit

The best test accuracy was 0.8715 with k= 7

The corresponding training accuracy obtained was : 0.893875

2.2.12 Model Evaluation - Jaccard Index, F1 Score, Model Accuracy & Confusion Matrix

Model Accuracy : It measures the accuracy of the classifier based on the predicted labels and the true labels and is defined as :

\[\begin{array}{c} \alpha(y, \hat{y})=\frac{|y \cap \hat{y}|}{|\hat{y}|}=\frac{\text { No. of Correctly Classified Predictions }}{\text { Total No. of Predictions }} \end{array}\]Jaccard Index :

Given the predicted values of the target variable as \((\hat{y})\) and true/actual values as \(y\), the Jaccard index is defined as :

Simplifying,

\[\begin{array}{c} j(y, \hat{y})==\frac{\text { No. of Correctly Classified Predictions }}{\text { No. of True Samples }+\text { No. of Predicted Samples }-\text { No. of Correctly Classified Predictions }} \end{array}\]Confusion Matrix :

The confusion matrix is used to provide information about the performance of a categorical classifier on a set of test data for which true values are known beforehand.

| Actual Values | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predicted Values | Positive (1) | Negative (0) |

| Positive (1) | True Positive (TP) | False Positive (FP) |

| Negative (0) | False Negative (FN) | True Negative (TN) |

The following information can be extracted from the confusion matrix:

- True Positive (TP) : Model correctly predicted Positive cases as Positive. Disease is diagnosed as present and truly is present.

- False Positive (FP) : Model incorrectly predicted Negative cases as Positive. Disease is diagnosed as present and but is actually absent. (Type I error)

- False Negative (FN) : Model incorrectly predicted Positive cases as Negative. Disease is diagnosed as absent but is actually present. (Type II error)

- True Negative (TN) : Model correctly predicted Negative cases as Positive. Disease is diagnosed as absent and is truly absent.

F1 Score :

The F1 score is a measure of model accuracy & is calculated based on the precision and recall of each category by obtaining the weighted average of the Precision and Sensitivity (Recall). Precision is the ratio of correctly labelled samples to all samples & Recall is a measure of the frequency in which the positive predictions are taking place.

\[\text { Precision }=\frac{T P}{T P+F P}\] \[\text { Recall (Sensitivity) }=\frac{T P}{T P+F N}\] \[F 1 \text { Score }=2\left(\frac{\text { Precision } \times \text { Recall }}{\text { Precision }+\text { Recall }}\right)\]# First,we keep a dictionary that measures all the losses/scores for our model/classifier

Test_Scores={}

Train_Scores={}

# Now evaluate the model based on metrics

# First import scoring methods

from sklearn.metrics import jaccard_similarity_score, accuracy_score, f1_score, confusion_matrix,precision_score, recall_score

# reconstruct the best model as last model is only saved. Previous models were overwritten

best_k=mean_acc.argmax()+1 #7

neigh = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors = best_k).fit(X_train,y_train)

yhat=neigh.predict(X_test)

y_pred=neigh.predict(X_train)

# training scores

Train_Scores['KNN-jaccard']=jaccard_similarity_score(y_train, y_pred)

Train_Scores['KNN-f1-score']=f1_score(y_train, y_pred, average='weighted')

Train_Scores['KNN-accuracy-score']=accuracy_score(y_train, y_pred)

Train_Scores['KNN-precision-score']=precision_score(y_train, y_pred,average='weighted')

Train_Scores['KNN-recall-score']=recall_score(y_train, y_pred,average='weighted')

print("Train Scores")

print(Train_Scores)

# testing scores

Test_Scores['KNN-jaccard']=jaccard_similarity_score(y_test, yhat)

Test_Scores['KNN-f1-score']=f1_score(y_test, yhat, average='weighted')

Test_Scores['KNN-accuracy-score']=accuracy_score(y_test, yhat)

Test_Scores['KNN-precision-score']=precision_score(y_test, yhat, average='weighted')

Test_Scores['KNN-recall-score']=recall_score(y_test, yhat, average='weighted')

print("Test Scores")

print(Test_Scores)

{'KNN-jaccard': 0.893875, 'KNN-f1-score': 0.8934953484075454, 'KNN-accuracy-score': 0.893875, 'KNN-precision-score': 0.8941695756701838, 'KNN-recall-score': 0.893875}

Test Scores

{'KNN-jaccard': 0.8715, 'KNN-f1-score': 0.8708624433676339, 'KNN-accuracy-score': 0.8715, 'KNN-precision-score': 0.8716530002545858, 'KNN-recall-score': 0.8715}

cf_matrix=confusion_matrix(y_test, yhat) # get the confusion matrix

side_of_cm=cf_matrix.shape[0] # get the side of the square confusion matrix

group_counts = ["{0:0.0f}".format(value) for value in cf_matrix.flatten()]

group_percentages = ["{0:.2%}".format(value) for value in cf_matrix.flatten()/np.sum(cf_matrix)]

# get the value counts and their corresponding percentages

labels = [f"{v2}\n{v3}" for v2, v3 in

zip(group_counts,group_percentages)]

# get the labels to be attached to the plot for the confusion matrix

labels = np.asarray(labels).reshape(side_of_cm,side_of_cm)

# set the figure size

fig=plt.figure(figsize=(20,8))

# seaborn plot for confusion matrix

sns.heatmap(cf_matrix, annot=labels, fmt='', cmap='inferno')

# plot metadata

plt.xlabel("True Values",fontsize=18)

plt.ylabel("Predicted Values",fontsize=18)

plt.xticks(fontsize=16)

plt.yticks(fontsize=16)

plt.title("Confusion Matrix for k-NN classifier for applied t-SNE\nMNIST Handwritten Digit Dataset",fontsize=20)

Note to the reader :

The implementation of the k-NN classifier over the t-SNE applied MNIST dataset has been shown only for two component t-SNE and not for the three component t-SNE, as the code is similar and borrowed from the former workflow. The latter code is left to the reader for implementation practice.

2.2.13 Limitations of the t-SNE Algorithm

Although particularly well suited for visualization of high-dimensional dataset visualizations, there exist the following pitfalls of t-SNE :

- t-SNE scales QUADRATICALLY in the number of objects $N$ and hence it is COMPUTATIONALLY EXPENSIVE & MEMORY INEFFICIENT.

- As compared to other dimensionality reduction algorithms, it is often very time consuming and beyond a thousand objects, it is found to be TOO SLOW TO BE PRACTICAL.

- Often in the case of very high dimensional data, you may need to APPLY ANOTHER DIMENSIONALITY REDUCTION TECHNIQUE (such as PCA for dense data or TruncatedSVD for sparse data) before using t-SNE.

2.3 Principle Component Analysis (PCA)

Objective :

Introduce UCI Breast Cancer Dataset to perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and use projected features to train and test a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier.

2.3.1 The UCI Breast Cancer Dataset

This algorithms defined in this section will be based upon the University of California, Irvine (UCI) Breast Cancer Dataset. For each cell the dataset contains ten real valued input features.

- radius (mean of distances from center to points on the perimeter)

- texture (standard deviation of gray-scale values)

- perimeter

- area

- smoothness (local variation in radius lengths)

- compactness (\(\frac{perimeter^{2}}{area - 1.0}\))

- concavity (severity of concave portions of the contour)

- concave points (number of concave portions of the contour)

- symmetry

- fractal dimension (coastline approximation-1.0)

The features obtained from these inputs are captured in the dataframe shown at the end of this section’s code snippet.

About Breast Cancer :

Breast Cancer develops in breast cells. It can occur in both men and women, though after skin cancer it’s one of the most common cancer diagnosed in females. It begins when the cells in the breast start to expand uncontrollably. Eventually these cells form tumors that can be detected via X-Ray or felt as lumps near the breast area.

The main challenge is to classify these tumors into malignant (cancerous) or benign (non cancerous). A tumor is considered as mailgnant if the cells expand into adjacent tissues or migrate to distant regions of the body. A benign tumor doesn’t occupy any other nearby tissue or spread to other parts of the body like the way cancerous tumors can. But benign tumors may be extreme if the structure of heart muscles or neurons is pressurized.

Machine Learning technique can significantly improve the level of breast cancer diagnosis. Analysis shows that skilled medical professionals can detect cancer with 79% precision, while machine learning algorithms can reach 91% (sometimes up to 97%) accuracy.

Information on Breast Cancer:

For more information visit Wikipedia : Breast Cancer.

Importing the Dataset :

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer # scikit learn has an inbuilt dataset library which includes the breast cancer dataset

cancer = load_breast_cancer() # load the cancer dataset form sklearn library

Let’s view the data in a dataframe:

col_names = list(cancer.feature_names) # create a column names of the list of all the variables and add features

col_names.append('target') # append the target variable to column names

df = pd.DataFrame(np.c_[cancer.data, cancer.target], columns=col_names) # concatenate the columns using the np.c_ function

Construct a column named label that contains the string values of the target mapping :

1.0 = Benign (non cancerous).0.0 = Malignant (cancerous).

df['label'] = df['target'].map({0 :'Malignant', 1 : 'Benign'}) # mapping the numerical variables to string target names

print("Shape of df :",df.shape) # display the shape of the dataframe

df.tail(4) # list the last 4 rows in the dataframe

Shape of df : (569, 32)

| mean radius | mean texture | mean perimeter | mean area | mean smoothness | mean compactness | mean concavity | mean concave points | mean symmetry | mean fractal dimension | radius error | texture error | perimeter error | area error | smoothness error | compactness error | concavity error | concave points error | symmetry error | fractal dimension error | worst radius | worst texture | worst perimeter | worst area | worst smoothness | worst compactness | worst concavity | worst concave points | worst symmetry | worst fractal dimension | target | label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 565 | 20.13 | 28.25 | 131.20 | 1261.0 | 0.09780 | 0.10340 | 0.14400 | 0.09791 | 0.1752 | 0.05533 | 0.7655 | 2.463 | 5.203 | 99.04 | 0.005769 | 0.02423 | 0.03950 | 0.01678 | 0.01898 | 0.002498 | 23.690 | 38.25 | 155.00 | 1731.0 | 0.11660 | 0.19220 | 0.3215 | 0.1628 | 0.2572 | 0.06637 | 0 | Malignant |

| 566 | 16.60 | 28.08 | 108.30 | 858.1 | 0.08455 | 0.10230 | 0.09251 | 0.05302 | 0.1590 | 0.05648 | 0.4564 | 1.075 | 3.425 | 48.55 | 0.005903 | 0.03731 | 0.04730 | 0.01557 | 0.01318 | 0.003892 | 18.980 | 34.12 | 126.70 | 1124.0 | 0.11390 | 0.30940 | 0.3403 | 0.1418 | 0.2218 | 0.07820 | 0 | Malignant |

| 567 | 20.60 | 29.33 | 140.10 | 1265.0 | 0.11780 | 0.27700 | 0.35140 | 0.15200 | 0.2397 | 0.07016 | 0.7260 | 1.595 | 5.772 | 86.22 | 0.006522 | 0.06158 | 0.07117 | 0.01664 | 0.02324 | 0.006185 | 25.740 | 39.42 | 184.60 | 1821.0 | 0.16500 | 0.86810 | 0.9387 | 0.2650 | 0.4087 | 0.12400 | 0 | Malignant |

| 568 | 7.76 | 24.54 | 47.92 | 181.0 | 0.05263 | 0.04362 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.1587 | 0.05884 | 0.3857 | 1.428 | 2.548 | 19.15 | 0.007189 | 0.00466 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.02676 | 0.002783 | 9.456 | 30.37 | 59.16 | 268.6 | 0.08996 | 0.06444 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.2871 | 0.07039 | 1 | Benign |

Alternative :

You can also run the following code, provided you have cloned our github repository.

df= pd.read_excel("/content/DIMENSIONALITY_REDUCTION/data/UCI_Breast_Cancer_Data.xlsx")

Also, with a working internet connection, you can run :

df= pd.read_excel("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/khanfarhan10/DIMENSIONALITY_REDUCTION/master/data/UCI_Breast_Cancer_Data.xlsx")

–OR–

df= pd.read_excel("https://github.com/khanfarhan10/DIMENSIONALITY_REDUCTION/blob/master/data/UCI_Breast_Cancer_Data.xlsx?raw=true")

2.3.2 Perform Basic Data Visualization :

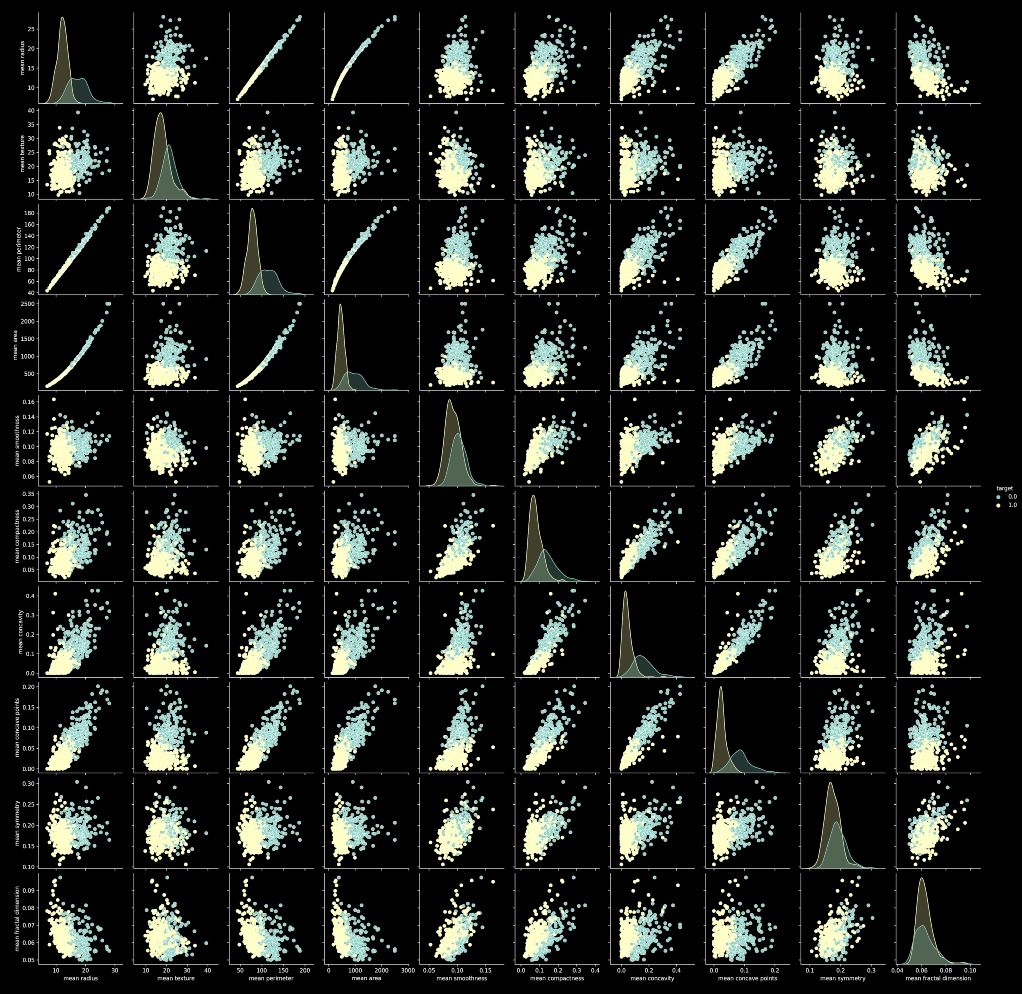

Pair Plot :

A pairplot is a combinational plot of both histograms and scatterplots. A scatterplot is used to show the relation between different input features. In a scatterplot every datapoint is represented by a dot. The histograms on the diagonal show the distribution of a single variable where the scatter plots on the upper and lower triangle show the relation between two variables.

sns.pairplot(df, hue='target', vars=['mean radius', 'mean texture', 'mean perimeter', 'mean area',

'mean smoothness', 'mean compactness', 'mean concavity',

'mean concave points', 'mean symmetry', 'mean fractal dimension'],

palette=sns.color_palette("tab10",2))

# create scattterplot using Seaborn

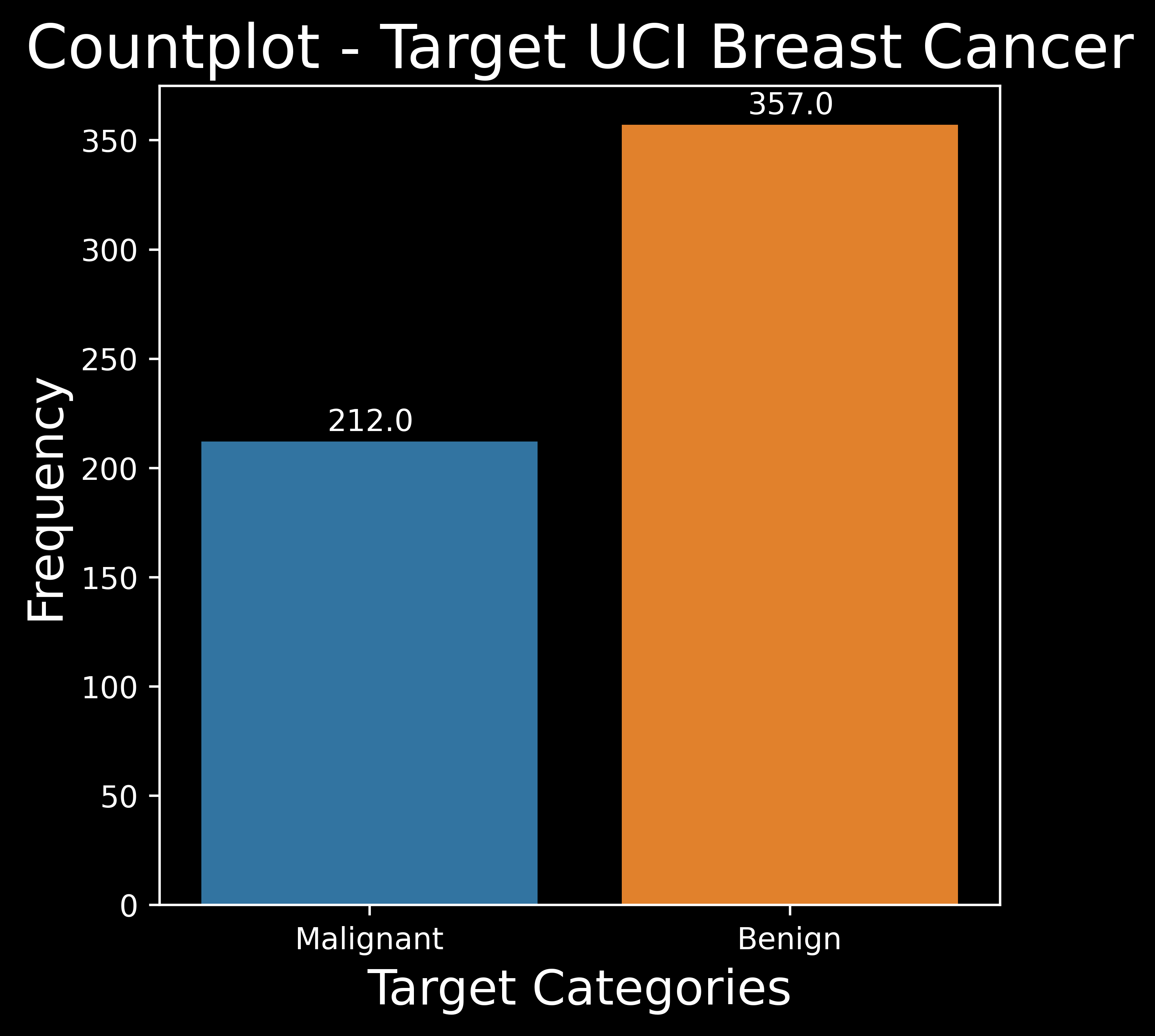

Count Plot :

A countplot counts the number of observations for each class of target variable and shows it using bars on each categorical bin.

fig = plt.figure(figsize= (5,5)) # create figure with required figure size

categories=["Malignant","Benign"] # declare the categories of the target variable

ax = sns.countplot(x='label',data=df,palette=sns.color_palette("tab10",len(categories)))

# create countplot from the Seaborn Library

# set plot metadata

plt.title('Countplot - Target UCI Breast Cancer',fontsize=20) # set the plot title

plt.xlabel('Target Categories',fontsize=16) # set the x labels & y labels

plt.ylabel('Frequency',fontsize=16)

for p in ax.patches:

ax.annotate('{:.1f}'.format(p.get_height()), (p.get_x()+0.3, p.get_height()+5))

# put the counts on top of the bar plot

Data Visualization Note :

Note that in all the data visualization plots :

1.0 (Orange)is used to representBenign (non cancerous).0.0 (Blue)is used to representMalignant (cancerous).

2.3.3 Create Training and Testing Dataset

Extract the Dataset into Input Feature Variables in \(X\) & Output Target Variable in \(y\).

X = df.drop(['target','label'], axis=1) # drop 2 colums : target is numerical (1/0) and label is string (Malignant/Benign)

y = df.target # store the numerical target into y : 0 for Malignant and 1 for Benign

print("Shape of X :",X.shape,"Shape of y :",y.shape) # display the variable shapes

Shape of X : (569, 30) Shape of y : (569,)

2.3.4 Principal Component Analysis (PCA) : An Introduction

In higher dimensions, where it isn't possible to find out the patterns between the data points of a dataset, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) helps to find out the correlation and patterns between the data points of the dataset so that the data can be compressed from higher dimensional space to lower dimensional space by reducing number of dimensions without any loss of major key data.

This algorithms helps in better Data Intuition and Visualization and is efficient in segregating Linearly Separable Data.

Chronological Steps to compute PCA :

- Transposing the Data for Usage into Python

- Standardization - Finding the Mean Vector

- Computing the n-dimensional Covariance Matrix

- Calculating the Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors of the Covariance Matrix

- Sorting the Eigenvalues and Corresponding Eigenvectors Obtained

- Construct Feature Matrix - Choosing the k Eigenvectors with the Largest Eigenvalues

- Transformation to New Subspace - Reducing Number of Dimensions

We will go through each step in great detail in the following sections.

2.3.5 Transposing the Data for Usage into Python

Interchanging the rows with columns and vice-versa is termed as the transpose of a matrix.

Mathematically,

\[X_{m \times n}=|a_{ij}|,\text {for } i,j \text { }\epsilon \text { } m,n\] \[X^{T}_{n \times m}=|a_{ji}|,\text {for } i,j \text { }\epsilon \text { } m,n\]X_Transposed=X.T # create Transpose of the X matrix using numpy .T method

print("Shape of Original Data (X) :",X.shape,"Shape of Transposed Data (X_Transposed) :",X_Transposed.shape) # display shapes

Shape of Original Data (X) : (569, 30) Shape of Transposed Data (X_Transposed) : (30, 569)

2.3.6 Standardization - Finding the Mean Vector

Here we will use a slightly different approach for standardizing the dataset. By subtracting the mean from each variable value we will have standardized all of the input features.

\[\text{standardized variable value}=\text{initial variable value}-\text{mean value}\]Mathematically,

\[X^{\prime}=X-\mu\]mean_vec = np.mean(X_Transposed,axis=1).to_numpy().reshape(-1,1) # get the mean vector with proper shape

X_std = X_Transposed - mean_vec # standardize the data

print("Shape of mean vector (mean_vec) :", mean_vec.shape, "Shape of standardized vector (X_std) :", X_std.shape) # display shapes

Shape of mean vector (mean_vec) : (30, 1) Shape of standardized vector (X_std) : (30, 569)

2.3.7 Computing the n-dimensional Covariance Matrix

Covariance is a statistical method used to measure how two random variables vary with respect to each other & is used in n-dimensions where \(n \geq 2\). In one dimension, Covariance is similar to variance where we determine single variable distributions.

For n number of features, Covariance is calculated using the following formula:

\[cov(x,y)=\frac{\sum\left(x_{i}-\bar{x}\right)\left(y_{i}-\bar{y}\right)}{n-1}\]\(cov(x,y)\) = covariance between variable \(x\) and \(y\)

\(x_{i}\) = data value of \(x\)

\(y_{i}\) = data value of \(y\)

\(\bar{x}\) = mean of \(x\)

\(\bar{y}\) = mean of \(y\)

\(n\) = number of data values

Note that \(cov(x,y) = cov(y,x)\), hence the covariance matrix is symmetric across the central diagonal. Also, \(covariance(x,x) = variance(x)\).

\[S^{2}=\frac{\sum\left(x_{i}-\bar{x}\right)^{2}}{n-1}\]where,

\(S^{2}=\) sample variance

\(x_{i}=\) the value of the one observation

\(\bar{x}=\) the mean value of all observations

\(n=\) the number of observations

For 3-dimensional datasets (dimensions \(x\),\(y\),\(z\)) we have to calculate \(cov(x,y)\), \(cov(y,z)\) & \(cov(x,z)\) and the covariance matrix will look like

\[\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \operatorname{Cov}(x, x) & \operatorname{Cov}(x, y) & \operatorname{Cov}(x, z) \\ \operatorname{Cov}(y, x) & \operatorname{Cov}(y, y) & \operatorname{Cov}(y, z) \\ \operatorname{Cov}(z, x) & \operatorname{Cov}(z, y) & \operatorname{Cov}(z, z) \end{array}\right]\]& similar calculations follow for higher order datasets. for n-dimensional datasets, number of covariance values = \(\frac{n!}{2(n-2)!}\)

X_covariance=np.cov(X_Transposed) # obtain the covariance matrix using .cov method of numpy

print("Shape of Covariance Matrix (X_covariance) :",X_covariance.shape) # display shapes

Shape of Covariance Matrix (X_covariance) : (30, 30)

2.3.8 Calculating the Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors of the Covariance Matrix

EigenValues :

A Covariance Matrix is always a square matrix, from which we calculate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

Let Covariance Matrix be denoted by \(C\), then the characteristic equation of this covariance matrix is

\(|C-\lambda I| = 0\)

The roots (i.e. \(\lambda\) values) of the characteristic equation are called the eigenvalues or characteristic roots of the square matrix \(C_{n\times n}\).

Therefore eigenvalues of \(C\) are roots of the characteristic polynomial \(\Delta (C-λI) = 0\)

EigenVectors :

A non-zero vector \(X\) such that \((C-\lambda I) X = 0\) or \(C X = \lambda X\) is called an eigenvector or characteristic vector corresponding to this lambda of matrix \(C_{n\times n}\).

X_eigvals, X_eigvecs = np.linalg.eig(X_covariance) # Calculate the eigenvectors and eigenvalues using numpy's linear algebra module

print("Shape of eigen values :",X_eigvals.shape,"Shape of eigen vectors :",X_eigvecs.shape) # display shapes

Shape of eigen values : (30,) Shape of eigen vectors : (30, 30)

2.3.9 Sorting the Eigenvalues and Corresponding Eigenvectors Obtained

The eigenvector of the Covariance Matrix with the highest eigenvalues are to be selected for calculating the Principal Component of that dataset.

In this way we have to find out the eigenvalues of that Covariance Matrix in a DESCENDING order. Here we will attempt to sort the eigenvalues along with their corresponding eigenvectors using a Pandas dataframe.

eigen_df=pd.DataFrame(data=X_eigvecs,columns=X_eigvals) # create a pandas dataframe of the eigenvalues and the eigen vectors

eigen_df_sorted = eigen_df.reindex(sorted(eigen_df.columns,reverse=True), axis=1) # sort the df columns in a DESCENDING order

print("Shape of original eigen dataframe (eigen_df):",eigen_df.shape,

"Shape of sorted eigen dataframe (eigen_df_sorted):",eigen_df_sorted.shape) # print shapes

eigen_df_sorted.head(3) # display the first 3 rows in dataframe

Shape of original eigen dataframe (eigen_df): (30, 30) Shape of sorted eigen dataframe (eigen_df_sorted): (30, 30)

| 4.437826e+05 | 7.310100e+03 | 7.038337e+02 | 5.464874e+01 | 3.989002e+01 | 3.004588e+00 | 1.815330e+00 | 3.714667e-01 | 1.555135e-01 | 8.406122e-02 | 3.160895e-02 | 7.497365e-03 | 3.161657e-03 | 2.161504e-03 | 1.326539e-03 | 6.402693e-04 | 3.748833e-04 | 2.351696e-04 | 1.845835e-04 | 1.641801e-04 | 7.811020e-05 | 5.761117e-05 | 3.491728e-05 | 2.839527e-05 | 1.614637e-05 | 1.249024e-05 | 3.680482e-06 | 2.847904e-06 | 2.004916e-06 | 7.019973e-07 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.005086 | 0.009287 | -0.012343 | -0.034238 | -0.035456 | -0.131213 | 0.033513 | 0.075492 | -0.350549 | -0.139560 | -0.419347 | 0.735142 | 0.218087 | 0.081026 | 0.137866 | 0.141957 | -0.044213 | -0.089729 | 0.021006 | -0.080107 | 0.059475 | -0.008724 | 0.004578 | -0.028289 | -0.003596 | -0.001603 | -0.002793 | -0.003259 | 0.000513 | -0.000648 |

| 1 | 0.002197 | -0.002882 | -0.006355 | -0.362415 | 0.443187 | -0.213486 | -0.784253 | 0.068741 | 0.004084 | -0.076668 | 0.029017 | -0.001770 | 0.004231 | 0.001985 | -0.007075 | 0.003718 | 0.001744 | 0.000141 | 0.001250 | 0.000213 | -0.000508 | 0.000326 | -0.000571 | -0.000073 | -0.000432 | -0.000686 | -0.000203 | -0.000109 | 0.000129 | -0.000005 |

| 2 | 0.035076 | 0.062748 | -0.071669 | -0.329281 | -0.313383 | -0.840324 | 0.189075 | -0.083964 | 0.132828 | 0.089211 | 0.002689 | -0.081781 | -0.025118 | -0.005229 | -0.013443 | -0.020684 | 0.010828 | 0.013778 | -0.000616 | 0.010940 | -0.010015 | 0.003179 | -0.001251 | 0.003584 | 0.000308 | 0.000134 | -0.000148 | 0.000592 | -0.000283 | 0.000153 |

2.3.10 Construct Feature Matrix - Choosing the k Eigenvectors with the Largest Eigenvalues

Now that we have sorted the eigenvalues, we can get a Matrix that contributes to the Final Principal Components of that dataset in the respective order of significance. The components with lesser importance (corresponding eigenvectors with lesser magnitude of eigenvalues) can be ignored. With these selected eigenvectors of the Covariance Matrix a Feature Vector is constructed.

Here we will attempt to choose the top number of components(k), in our case number of components (no_of_comps) =2.

no_of_comps = 2 # select the number of PCA components

feature_matrix = eigen_df_sorted.iloc[:, 0 : no_of_comps] # extract first k cols from the sorted dataframe

print("Shape of Feature Matrix (feature_matrix):",feature_matrix.shape) # display shape of feature matrix

feature_matrix.head(4) # display first 4 rows of the feature matrix

Shape of Feature Matrix (feature_matrix): (30, 2)

| 443782.605147 | 7310.100062 | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.005086 | 0.009287 |

| 1 | 0.002197 | -0.002882 |

| 2 | 0.035076 | 0.062748 |

| 3 | 0.516826 | 0.851824 |

2.3.11 Data Transformation - Derivation of New Dataset by PCA - Reduced Number of Dimensions

The new dataset is derived simply by dot multiplication of the transpose of the standardized data on the right with the feature vector on the right.

\[\text {Final Transformed PCA Data}=\text{Data Standardized}^T \cdot \text {Feature Vector}\]Final_PCA = X_std.T.dot(feature_matrix_numpy)

# perform transpose of the Standardized Data & operate dot product with feature matrix

print("Shape of Final PCA Data :",Final_PCA.shape) # display the shape of PCA

Shape of Final PCA Data : (569, 2)

2.3.12 PCA using Scikit-Learn

All the tasks mentioned above can be performed using PCA() that is an in-built function of scikit learn library to reduce the dimensions of a dataset.

Here we have performed PCA analysis with our data using n_components = 2. The n-components parameter denotes the number of principal components (components with higher significance that means these components have higher eigenvalues corresponding to its eigenvectors as performed stepwise before).

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA # import the PCA algorithm from the Scikit-Learn Library

pca = PCA(n_components= 2) # choose the number of components for PCA

X_PCA = pca.fit_transform(X) # fit the PCA algorithm

print("Shape of Scikit Learn PCA :",X_PCA.shape) # display the shapes of the PCA obtained via Scikit - Learn

Shape of Scikit Learn PCA : (569, 2)

2.3.14 Verification of Library & Stepwise PCA

In this section we will verify that the PCA obtained from our steps are the same as the PCA from the Scikit-Learn Library.

For this procedure we will consider that the two PCAs are not identiacal but lie very very close to each other, acccounting for errors crept in due to Rounding Off (Rounding Errors). Hence if the true value is \(T\) and the observed value \(O\) is within the range \((T \pm \delta)\) then the observed value is considered nearly equal to the true value, where \(\delta\) is the allowed tolerance value, set to a very small positive value.

Mathematically, \(T-\delta<O<T+\delta\) yields to true, else false.

In other words, we check for : \(|T-O| \leq \delta\)

We perform this verification using the allclose function of numpy :

print(np.allclose(X_PCA, Final_PCA,rtol=0, atol=1e-08))

# use zero relative tolerance and a suitably low value of absolute tolerance to verify that the values obtained Theoretically & Practically Match

True

Now we know that the value of the theoretic PCA calculated from the Stepwise Calculation Matches the PCA from the Scikit Learn Library. However, since there are various steps that are extensive in nature, we will now use the SkLearn PCA henceforth.

2.3.15 PCA - Captured Variance and Data Lost

Explained Variance Ratio is the ratio between the variance attributed by each selected principal component and the total variance. Total variance is the sum of variances of all individual principal components. Multiplying this explained variance ratio with 100%, we get the percentage of variance ascribed by each chosen principal component & subtracting the sum of variances from 1 gives us the total loss in variance.

Hence, the PCA Components Variance are as follows :

round_to=2 # round off values to 2

explained_variance = pca.explained_variance_ratio_ # get the explained variance ratio

# perform pretty display of ratio percentages

for i,e in enumerate(explained_variance):

print("Principal Component",i+1,"- Explained Variance Percentage :" , round(e*100,round_to))

total_variance=explained_variance.sum() # get the total sum of the variance ratios obtained

print("Total Variance Percentage Captured :",round(total_variance*100,round_to))

var_loss=1 - total_variance # calculate the loss in variance

print("Total Variance Percentage Loss :",round(var_loss*100,round_to))

Principal Component 1 - Explained Variance Percentage : 98.2

Principal Component 2 - Explained Variance Percentage : 1.62

Total Variance Percentage Captured : 99.82

Total Variance Percentage Loss : 0.18

Note to the reader :

The explained variance and data loss part for 3 component PCA is left as a practice activity to the reader.

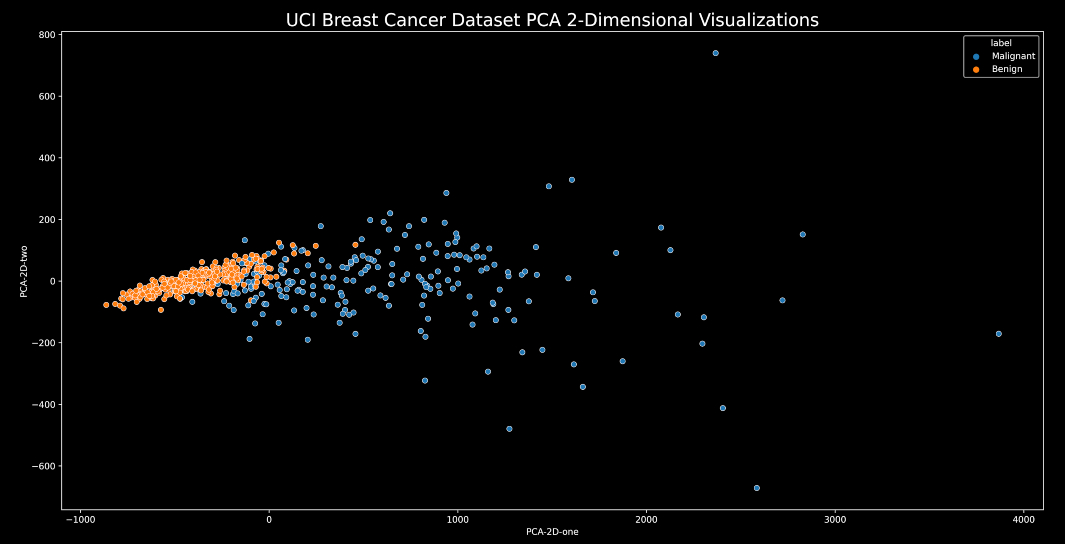

2.3.16 PCA Visualizations

Visual Insights to PCA on the Breast Cancer Dataset will help us understand breast cancer classification in a better way and is definitely an essential requirement for better Data Insights.

Dataframe Preparation :

First we will prepare the pandas dataframe for visualizing the 2-D and 3-D Principal Components after applying PCA with the respective number of components (n_components).

pca_2d = PCA(n_components= 2) # use 2-component PCA

PCA_2D = pca_2d.fit_transform(X) # fit the 2-component PCA

pca_3d = PCA(n_components= 3) # use 3-component PCA

PCA_3D = pca_3d.fit_transform(X) # fit the 3-component PCA

print("Shape of PCA 2D :",PCA_2D.shape,"Shape of PCA 3D :",PCA_3D.shape) # display shapes

Shape of PCA 2D : (569, 2) Shape of PCA 3D : (569, 3)

PCA_df = pd.DataFrame(data = np.c_[PCA_2D,PCA_3D]

, columns = ['PCA-2D-one', 'PCA-2D-two','PCA-3D-one', 'PCA-3D-two','PCA-3D-three'])

# create a dataframe of the applied PCA in 2-D & 3-D

PCA_df["label"]=df["label"] # assign label column to previously assigned labels

print("Shape of PCA dataframe",PCA_df.shape) # display shape of resulting PCA dataframe

PCA_df.tail(4) # display the last 4 rows in the dataframe

Shape of PCA dataframe (569, 6)

| PCA-2D-one | PCA-2D-two | PCA-3D-one | PCA-3D-two | PCA-3D-three | label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 565 | 1045.018854 | 77.057589 | 1045.018854 | 77.057589 | 0.036669 | Malignant |

| 566 | 314.501756 | 47.553525 | 314.501756 | 47.553525 | -10.442407 | Malignant |

| 567 | 1124.858115 | 34.129225 | 1124.858115 | 34.129225 | -19.742087 | Malignant |

| 568 | -771.527622 | -88.643106 | -771.527622 | -88.643106 | 23.889032 | Benign |

2-Dimensional Visualizations :

We will be using the scatterplot function from the seaborn library to get the required 2-D visualizations with some matplotlib customization.

plt.figure(figsize=(20,10)) # set the size of the figure

sns.scatterplot(data=PCA_df, x="PCA-2D-one", y="PCA-2D-two", hue='label', palette=sns.color_palette("tab10",len(categories)))

# make a scatterplot using Seaborn

plt.title("UCI Breast Cancer Dataset PCA 2-Dimensional Visualizations",fontsize=20) # set plot title

3-Dimensional Visualizations :

We will be using plotly to acheive interactive 3-D plotting as shown below with some random sampling to avoid overcrowded data points.

import plotly.express as px # use plotly for interactive visualizations

df_sampled= PCA_df.sample(n = 100,random_state=univ_seed) # perform random sampling over 100 points to get a subset of the original dataset

fig = px.scatter_3d(df_sampled, x='PCA-3D-one', y='PCA-3D-two', z='PCA-3D-three',

color='label', template="plotly_dark")

# chart a scatterplot

fig.write_html("UCI_Breast_Cancer_Dataset_PCA_3D_Viz.html") # save the figure for future uses

fig.show() # display the figure

2.3.17 Splitting the data into test and train sets

Before feeding data to the Machine Learning Model, perform train(80%)-test(20%) split :

X_train,X_test,y_train,y_test = train_test_split(PCA_2D,PCA_df["label"],test_size=0.2) # perform a 80%- 20% Train - Test Split

print("Shape of X_train :",X_train.shape,"Shape of y_train :",y_train.shape) # display shapes

print("Shape of X_test :",X_test.shape,"Shape of y_test :",y_test.shape)

Shape of X_train : (455, 2) Shape of y_train : (455,)

Shape of X_test : (114, 2) Shape of y_test : (114,)

Note to the Readers :

The procedure for classification using the 3 component PCA is left as a practice task for the Readers.

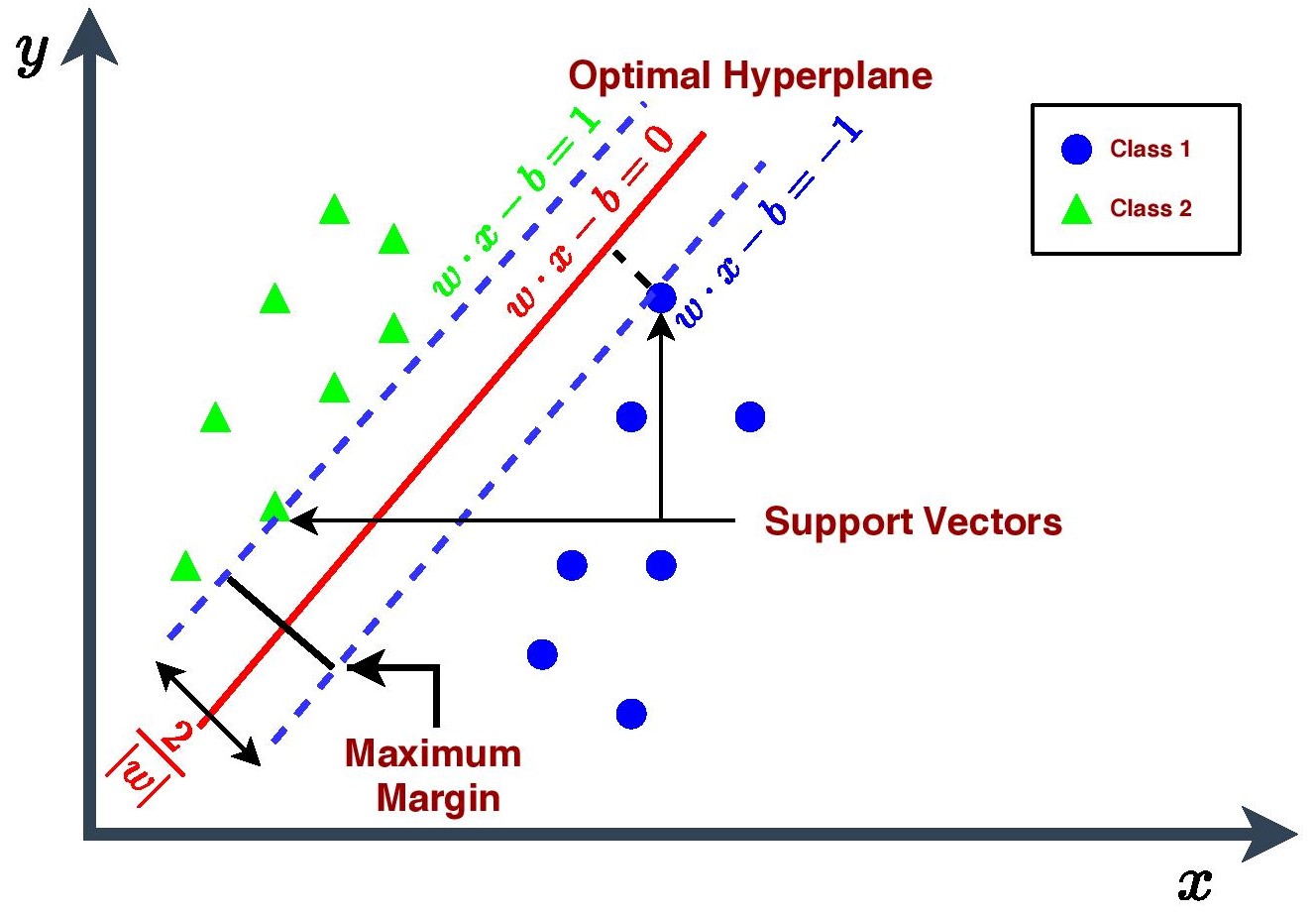

2.3.18 An Introduction to Classification Modelling with Support Vector Machines (SVM)

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are Supervised Machine Learning Algorithms that can be used for both Classification and Regression problems, though they are mostly used in classification problem to distinctly classify the data points.

The primary objective of an SVM Classifier is to find out a decision boundary in the n-dimensional space (where n is number of features) that will segregate the space into two regions where in one region the hypothesis predicts that y=1 and in another region the hypothesis predicts that y=0.

This decision boundary is also called a hyperplane. There could be many possible hyperplanes but the goal of SVM is to choose those extreme points or vectors which will help to create one hyperplane that will have maximum margin i.e. maximum distance between the data points of two regions or classes. The hyperplane with maximum margin is termed as optimal hyperplane. Those extreme points or vectors are called Support Vectors and hence, this algorithm is termed as Support Vector Machine.

Given a training data of \(n\) points : \(\left(\vec{x}_{i}, y_{i}\right)\) where \(y_{i}=0 \text{ or } 1\)

The Mathematical Formulation,

\[\min \frac{\|\vec{w} \|^{2}}{2} \quad \text { such that } y_{i}\left(\vec{w} \cdot x_{i}+b\right)-1 \geq 0 \quad \text { for } i=1 \ldots n\]where,

\[\vec{w} \text { is the normal vector to the hyperplane. }\] \[b \geq 0 \text { is the distance from the origin to the plane (or line).}\]

2.3.19 Types of SVM

Linear SVM :